Musing of a game cart bin hunter, in a world of repros and accessibility

As technology leaps forward, gaming constantly evolves into something grander and more immersive. But even amidst 4K resolutions and sprawling open worlds, there’s something magnetic about retro games that keeps pulling us back. For me, it’s more than just the games themselves—it’s the memories they carry. Whether it’s blowing into a dusty cartridge to make it work or spending entire Saturdays trying to beat Sonic the Hedgehog 2 with my brother, retro gaming connects me to a simpler, more joyful time.

Having attended several retro game fairs over the years, namely those Retrocons in Keeds, I’ve developed a bit of a ritual when I go. I’ll arrive early, head straight for the stalls with the boxes stacked haphazardly, and dig deep, hoping to find a hidden gem. If you’ve been to one, you know the drill: the hum of CRT TVs playing Super Mario Kart, tables piled high with Sega Mega Drive cases, and the endless buzz of chatter as collectors haggle over rare finds.

It’s akin to going bin hunting at a vinyl fair, looking for rare items or a bargain to complete a collection.

Cart digging

Retro game fairs are as much about the experience as they are about the games themselves. Walking through those packed aisles feels like time-traveling back to the golden age of gaming. I remember one fair where I stumbled across a near-mint copy of Streets of Rage 2 for the Mega Drive. Holding that case in my hands transported me straight to my childhood living room, where I first played it with my cousin on a summer afternoon.

Of course, these fairs aren’t just about nostalgia. They’re also where you meet fellow enthusiasts—people who understand the thrill of finding a loose Pokemon Red cartridge in a bargain bin or who’ll debate the merits of the NES over the Master System with you for hours.

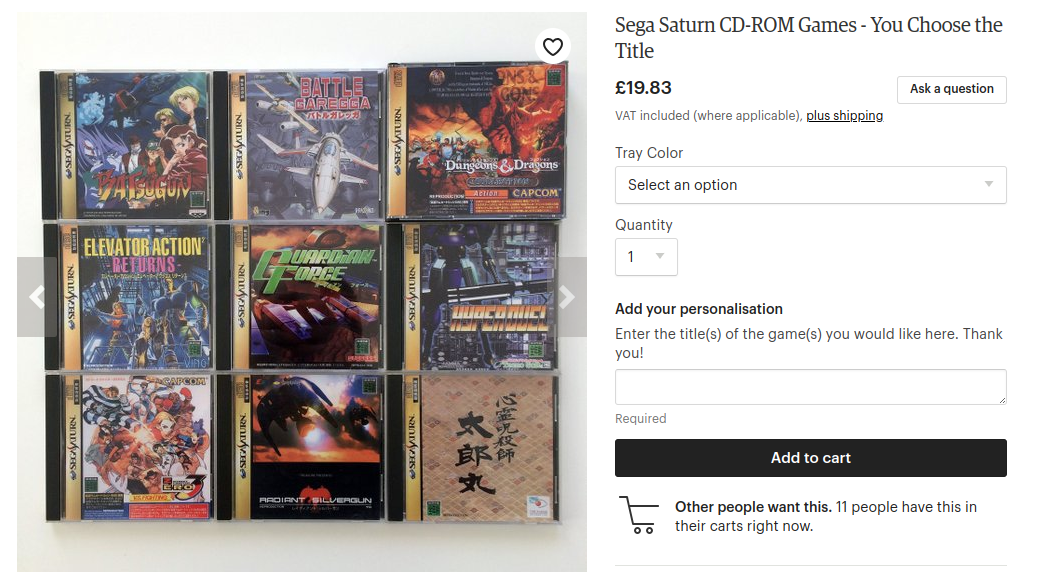

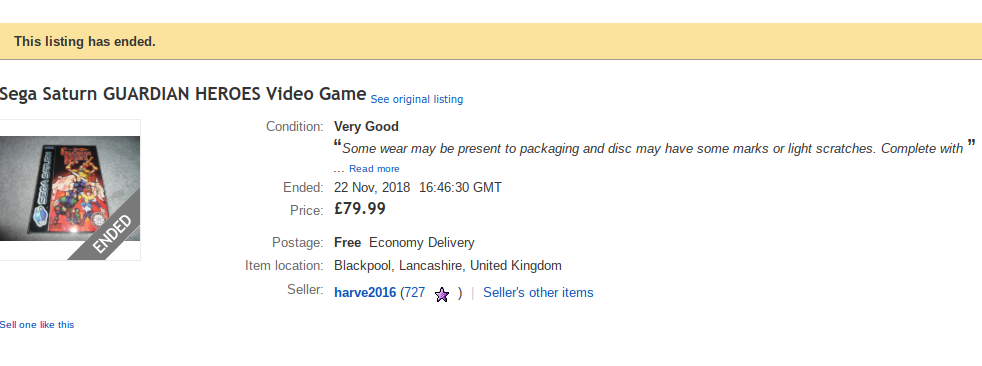

But not everything you find is authentic. As I’ve browsed through these fairs and online marketplaces, I’ve noticed more reproductions creeping in. Platforms like Etsy are full of reproductions of rare games, often cleverly disguised to look like the real thing. Sellers sometimes market them as “repros” in small print or use vague descriptions like “custom-made” to avoid legal trouble, leaving less experienced collectors at risk of overpaying for a fake.

For example, a reproduction of Earthbound might cost around £40, significantly less than an authentic cartridge, which can easily fetch over £200. While this makes collecting more accessible for those who just want to play the games, it raises ethical questions about transparency. Are these sellers preserving history or diluting it?

This debate also connects to the broader issue of game preservation. Many titles from the 8-bit and 16-bit eras are no longer commercially available, and their original physical media are deteriorating. This is where the ROM community steps in, often operating in a legal grey area to preserve games that might otherwise disappear entirely.

While downloading ROMs for games you don’t own is generally illegal, these communities argue that they’re archiving gaming history in the absence of meaningful efforts by publishers.

Whether you agree with them or not, their work sparks important conversations about who bears responsibility for preserving our gaming past.

“They don’t make ‘em like they used to”

What is it about retro games that keeps us coming back? For me, it’s their simplicity. There’s no 20-minute tutorial, no endless cutscenes—just pick up a controller and play. Titles like Super Metroid or Donkey Kong Country still hold up today because they were built on solid gameplay, not flashy gimmicks.

But beyond nostalgia, retro games are a window into gaming’s past. They remind us of a time when developers had to innovate within tight constraints—when 16 bits felt revolutionary, and the idea of saving your progress was a luxury. These games laid the foundation for everything that came after, and revisiting them gives us a deeper appreciation for how far gaming has come.